| |

Charlotte Bronte's Two Portraits

|

|

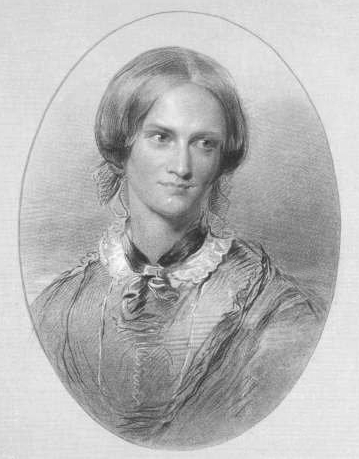

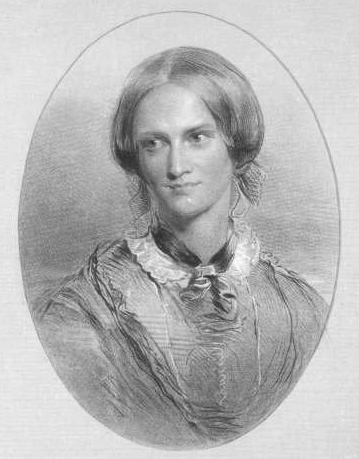

Two very different portraits of Charlotte Bronte exist. George Richmond's

(1850) remained hidden from public view but was published as an engraving in 1857. After the

death of Charlotte's widower in 1906 the original portrait passed to the National Portrait Gallery.

It was first exhibited in 1907 by which time it

had become firmly established as the public image of Charlotte.

In 1914 it was discovered that Charlotte's widower had hidden away a second

portrait. This was an 1830s group portrait of the sisters by their brother Branwell,

but Charlotte's appearance in this portrait was very different.1.

|

|

1850 - George

Richmond

|

|

Detail from George Richmond's portrait of Charlotte.

National Portrait

Gallery, London NPG 1452

After the death of her siblings, Charlotte's publisher requested portraits of

them but she replied that there were none. There were sketches and watercolours she had made of her

sisters, also Branwell's two group portraits, but she probably considered these

unworthy of publication. Another influence could have been the well documented fact that

Charlotte was very self-conscious about her own appearance. Shortly after this she travelled

to London and her publisher George Smith paid for the well-known society artist, George Richmond,

to create her now famous portrait.

|

|

|

Anne Bronte (left) and

Charlotte (right) in the 1830s group 'Pillar Portrait' by their

brother, Branwell.

|

When Charlotte first viewed the completed portrait she burst into tears because

it reminded her so much of her sister Anne who had died the previous year. Looking at portraits of

Anne it is clear why; she had an oval face and a Roman nose. George Smith asked if he could have a

copy made for himself, presumably for future publication.

When the portrait arrived at Haworth Parsonage there were mixed

views, on 2nd August 1850 Patrick Bronte wrote:

"The two portraits have, at length safely arrived, and have been as

safely hung up, in the best light and most favourable position. Without flattery the artist, in

the portrait of my daughter, has fully proved that the fame which he has acquired has been

fairly earned. Without ostentatious display, with admirable tact and delicacy, he has produced

a correct likeness, and succeeded in a graphic representation of mind as well as matter, and

with only black and white has given prominence and seeming life, and speech, and motion. I may

be partial, and perhaps somewhat enthusiastic, in this case, but in looking on the picture,

which improves upon acquaintance, as all real works of art do, I fancy I see strong indications

of the genius of the author of 'Shirley' and 'Jane Eyre'."

The portrait was a generous gift for Charlotte's father and this is

a letter thanking George Smith. Charlotte certainly seems to have been delighted with the

portrait.

When Charlotte died in 1855 there were no published portraits of her

or her family in the public domain and when it was suggested that one should

be used to illustrate her biography, her widower was opposed to the idea.

1a.

|

|

1857 - J

C Armytage

|

|

Publication of George Richmond's Portrait of Charlotte Bronte as an

engraving.

Engraving by Armytage of George Richmond's portrait of Charlotte,

1857.

Pressure was applied to Arthur Nicholls and he eventually he relented.

Charlotte's portrait was photographed, an engraving was made and it appeared in the biography

(1857). Here, Elizabeth Gaskell commented on this portrait and Branwell's group portrait of the

sisters.

She considered George Richmond's portrait to be "an admirable

likeness" but this is ambiguous, it could mean

"an admirable resemblance" or

"an admirable portrait." When

read in context it can only mean the latter because she then states that "those closest to

Charlotte" were "least satisfied with the resemblance" before going on to

praise Branwell's portrait.

She describes Branwell's 'Pillar Portrait' of his sisters as a poor painting but

was surprised by "...the striking resemblance which Charlotte ...

bore to her own representation, though it must have been ten years and more since the

portraits were taken. They were good likenesses, however badly

executed.” Charlotte would have been standing next to the portrait when Mrs

Gaskell viewed it in 1853 and these remarks imply that her appearance had changed very little in

twenty years.2.

The careful wording is perhaps partly due to Charlotte's widower

and the fact that Elizabeth Gaskell's publisher was George Smith, the man who had commissioned

the portrait seven years earlier. The pictures could easily depict two different women. If Gaskell

was correct then Branwell's oil painting is a poor portrait but the resemblance is good; Richmond's

is a good portrait but the resemblance is poor.

|

|

|

LEFT: Charlotte with an oval face and convex nose in

George Richmond's

portrait. RIGHT: Charlotte

with a square face and straight or concave nose in Branwell's 'Pillar Portrait'

|

When Arthur Nicholls Initially withheld permission to publish the portrait,

Ellen Nussey, in a letter to Elizabeth Gaskell, wrote that "there would always have been regret

for its painful expression to be perpetuated." A friend of Charlotte, Laetitia Wheelwright,

thought the portrait was "entirely flattering." Charlotte's

close friend, Mary Taylor, criticised the publication of a "flattered

likeness" lacking "the veritable square face" and

the "large, disproportionate nose." 3.

Mrs Pitt Byrne on George Richmond in general, and Charlotte's portrait:

"No one perhaps ever succeeded in that marvellous idealisation of a

sitter as George Richmond; he sets before him a man and lo! He makes him a poem, and what is

more inexplicable is that rare genius of his...there is no want of truthfulness to

nature. I don't know nor do I care whether he copies the features - between

ourselves I don't believe he does - but what of that? He gives you the mind, character, the

inner-self of his sitter, and always with a facile grace, which while it transfigures the

subject, still faithfully reproduces him... An example of this can be seen in the

pleasing portrait of Charlotte Bronte which he drew... with the bright eyes and charming

expression illuminating features that would otherwise have been

plain." 4.

In 1858, John Ruskin commented on his own portrait by George Richmond:

"You know I quite agree with the Daily News about the portrait. in fact,

I don't consider it a portrait at all, but merely a pleasant fancy of me by George

Richmond."

George Richmond painted "the truth, lovingly told" but Branwell

Bronte tried to achieve a true likeness.

|

|

John Hunter

Thompson.

|

|

It is clear by the comments made by Charlotte's friends that her portrait by

George Richmond is idealised and this is why it has not been used to compare with 'Charlotte' in

the photograph. There are many variations of the portrait but the first was the engraving by

Armytage (1857) for Smith, Elder.

|

J C Armytage's engraving

(reversed)

|

John Hunter Thompson's portrait of

Charlotte.

|

Charlotte's vibrant portrait by John Hunter Thompson is based on the engraving

by Armytage (there is a faint horizon line which does not exist in the original). Thompson may

have worked from a collodion photograph of the engraving as these were usually reversed images;

Charlotte's slightly crooked mouth turns down on the wrong side and her hair is parted on the wrong

side.

|

|

RETURN TO CONFUSING

PORTRAITS INDEX

|

|

|

|

|

1. George Richmond was interested in

physiognomy, as was Charlotte. In this extract from The Professor (a novel based

upon Charlotte's experiences in Brussels) she describes Frances Evans Henri: "You cannot tell

whether her nose was aquiline or retrousse, whether her chin was long or short, her face square or

oval; nor could I the first day, and it is not my intention to communicate to you at once a

knowledge I myself gained by little and little."

Charlotte

describing Frances Evans Henri in chapter 14 of The Professor (written in 1846 but unpublished;

edited & published posthumously in 1857).

1a. Barnard; Louise Barnard (29 March 2013).

"Brontë, Patrick Branwell". A Brontë Encyclopedia. Wiley.

p.263

"Most commentators agreed on the excellence of the

likenesses, despite the crudeness of Branwell’s artistic

techniques."

Ann Dinsdale, Brontë Parsonage Museum collections manager.

Keighley News 30 July 2015.

"Branwell’s famous portrait which is believed to show

a good likeness to the real-life Charlotte, Anne and

Emily."

2. There is other evidence that

Branwell managed to achieve a good likeness.

He had a brief career as an artist in Bradford from June

1838 until May 1839 lodging with the Kirby family and their niece, Margaret Hartley. In 1893 she

reminisced that “Whilst lodging with us he painted

my portrait and those of my uncle and aunt, and all three were accounted good

likenesses.” In 1858 William Davies visited Haworth

Parsonage, spoke at length with the Rev Patrick Bronte and on leaving was shown Branwell's

'Gun-Group' portrait of his sisters: “It was crude and

harsh from a technical point of view but the likenesses were said to be

good”

3. Letter from Mary Taylor to Mrs

Gaskell, 30th July 1857, Charlotte Bronte and Her Circle, Clement K. Shorter, 1896.

P.22

4. Gossip of the Century; Personal

and Traditional Memories - social, Literary, Artistic, &c Published in 4 Volumes by Mrs. Wm.

Pitt Byrne, 1892. Quoted by Mark Bostridge in 'CHARLOTTE BRONTE AND GEORGE RICHMOND -

Idealisation in the sitter' Bronte Society Transactions, Volume 17, Part 86, 1976 , pp.

58-60

|

|

|