|

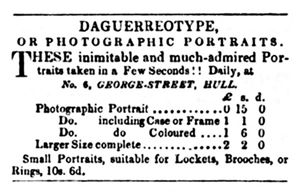

Could the Bronte Sisters have afforded a photograph in the

1840s? Daguerreotypes in England cost about a Guinea (£1.05p) throughout the 1840's,

including a frame or case. A group photo would probably have cost a little more. This was

about the same cost as having a miniature portrait painted but the advantage of the daguerreotype

was accuracy and detail.

Branwell's starting salary as an assistant railway clerk in

1840 was £75 p.a., rising to £130 the following year when he was promoted to clerk

in charge. Anne Bronte, employed as a governess at Thorp Green Hall near York,

was earning £40 p.a. in 1845 although she also had an income from railway

shares.

The Bronte family had never been wealthy but the sisters did come into money

after they were left a legacy from their Aunt Branwell (1843). This was about £300 each and was the

equivalent to three or four years wages for an office clerk. A large part of this legacy was

invested in (George Hudson's) York & North Midland Railway Shares. In 1845, it was paying a

dividend of 10% in line with the top railway companies.

George Hudson's York & North Midland Railway

Company was a great success, particularly in its early years when it was part of the trunk route to

London, via Derby and Birmingham.

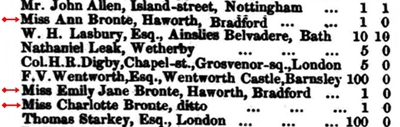

There was sufficient wealth in 1845 for Anne, Charlotte and Emily to donate

£1 each to the George Hudson Testimonial Fund. Hudson was a millionaire so

he certainly wasn't needy. The same year, Charlotte sent £10 to her

friend, Mary Taylor, who had emigrated to New Zealand.1.

The Bronte Sisters donation to the George Hudson

Testimonial Fund.

He was a popular man having created many private railways. To see the full list click

here.

|