| |

The 'Profile' Portrait - Emily or Anne?

|

|

The 'Profile Portrait' at the National Portrait Gallery.

The 'Profile Portrait' (NPG 1724) at the NPG is identified as Emily Bronte and

the reasons for this are given in the catalogue description. The conclusion is disputed because since

publication in the early 1970s further evidence has come to light. Some of the

main points are presented here.

|

|

The Physical

Evidence

|

|

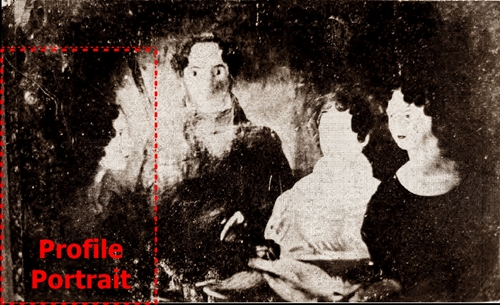

In the 1970s it was thought that all that remained of the

lost 'Gun Group' portrait of Branwell and his sisters was the 'Profile Portrait'

and three tracings.

There was an engraving of a 'Gun Group' but

this was thought at the time to be a "drawing by

Branwell," and treated as an unrelated second group. Ellen Nussey,

had identified the figures in this "drawing" and was probably correct, but this did not

mean that the sisters were in the same positions in the lost painting.

Almost 20 years after publication of the catalogue description, a

photograph of Branwell's original 'Gun Group' painting was discovered. It was now known

that the "drawing by Branwell" was actually an engraving, made in 1879 from

the photo. This meant that the newly discovered photo, the 'Profile

portrait,' the tracings, and the engraving, all relate to Branwell's

original 'Gun-Group' and that there had only ever been one. The

labelling of the tracings contradicts Ellen Nussey's labelling of the engraving.

1.

|

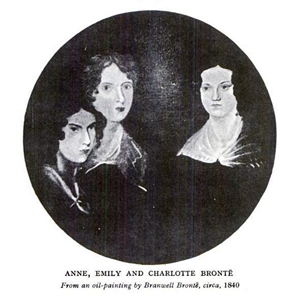

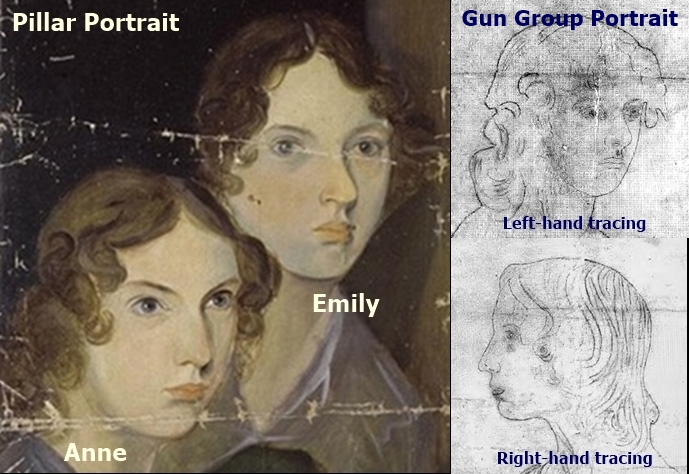

Tracings from the 'Gun Group' made either c1835 or

c1860. The sisters are identified

L-R:

Anne, Charlotte, Emily.

|

The 'Profile Portrait' at the NPG.

|

|

Copy of a photo taken c1858 but

not discovered until 1989, after publication of the NPG catalogue description.

This is the original 'Gun-Group' Portrait with 'Profile Portrait' figure on the far

right.

|

An engraving made from the photo and published in Haworth Past and Present,

1879.

|

|

A photo of the engraving with the

figures identified by Ellen Nussey as L-R:

Emily, Charlotte, Anne.

|

|

|

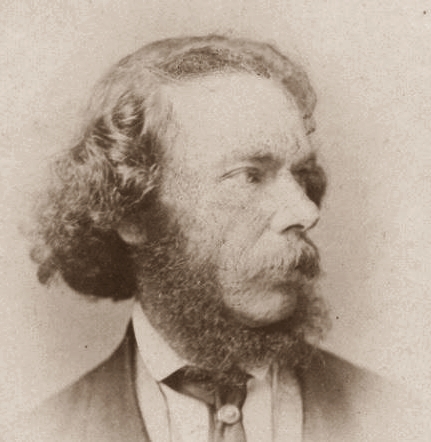

Arthur Bell Nicholls &

Clement King Shorter

|

|

Arthur Bell Nicholls

|

Clement King Shorter

|

The evidence supporting identification of

the 'Profile Portrait' as Emily has always been contradictory. The historian,

Clement Shorter, wrote (1896) that Mr Nicholls (Charlotte Bronte's widower):

“Being of opinion that the only accurate portrait [in the

Gun-Group] was that of Emily, he cut this out and destroyed the

remainder.” 2. The portrait found in Mr Nicholl's house in 1914, eight years after his

death, was the 'Profile Portrait' but this is the figure in the

engraving, identified by Martha Brown (1879) and Ellen Nussey (c1895) as Anne.

Shorter continued: “The portrait of Emily was given to Martha Brown, the servant, on one of

her visits to Mr. Nicholls.” This was

contradicted in 1914 by Mrs Nicholls stating that the painting had never left their

house in Ireland.3.It is also known that whilst Martha Brown did own a portrait

of Emily it was not an oil painting by Branwell but a pencil sketch by

Charlotte.

The Public Image.

These discrepancies are due in part to a refusal by Mr Nicholls

to acknowledge that any portrait of Charlotte existed other than the idealised 'Richmond

Portrait' (below) which he had authorised for publication in 1857. Shorter wasn’t aware of

this and took him at his word, to a degree. An example of this is when Shorter sent a photo of the

'Pillar Portrait' (above) to Mr Nicholls who replied "The likenesses are very bad - The

left hand corner has something of the expression of Anne - The others I should not

recognise." This is despite the fact that his deceased wife (Charlotte) is on the right.

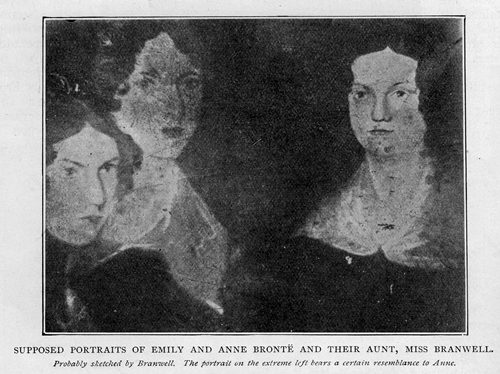

As a result Shorter published this image in Woman at Home in August 1897, identifying

her as her Aunt Branwell. Shorter had his own idea of what Emily looked like, hence the title in

capitals placing Emily to the left (this is Anne), but including in small italics "the

portrait on the extreme left bears a certain resemblance to Anne" so as not to contradict

Arthur Bell Nicholls.

Shorter made several visits to Mr Nicholls and corresponded with him for over 10

years, the subject of Bronte portraits often arising. During this entire period the original

portraits were languishing in a wardrobe upstairs in Mr Nicholl's house, but he said nothing; his

evasiveness exacerbated Shorter’s confusion.

This was demonstrated again in 1906 in a letter by Shorter to The

Times stating that only one photograph of Mr Nicholls existed when in fact there were at

least six.4. He went on to say that this

"one photo" which was published in his book, was taken at the time of Mr Nicholl’s

marriage to Charlotte in 1854. It was actually taken on his second marriage in 1864.

In 1914, when the 'Profile Portrait' was found in the wardrobe, it was

thought that this was the "portrait of Emily Bronte" seen by William Robertson Nicoll

when he visited Martha Brown in July 1879 and that it had somehow returned to Ireland after

her death in January 1880. The portrait of Emily owned by Martha was though a pencil

portrait by Charlotte and not an oil painting by Branwell.5.

In 1896 Clement Shorter had quoted Arthur Nicholls as saying

that the figure he had cut from the group was Emily. Whether he considered it an

error on his own part, or on that of Arthur Nicholls, by the 1920s he no longer trusted

his own account of their conversation nearly 30 years before. Nor did he have confidence in

Mrs Nicholls identification in 1914.

"the ... portrait of Emily... is really a portrait of Anne."

Ten years later Shorter stated that "the unique and valuable

portrait of Emily... is really a portrait of Anne." He was now convinced that the

National Portrait Gallery had wrongly identified the portrait... although he did not mention that

he was probably partly responsible for this. Clement Shorter died in 1927 and his

account from the 1890s has subsequently been quoted many times but ultimately he believed

it to be incorrect. 6.

|

|

Identification

- Mrs Nicholls

|

|

The 'Profile Portrait'

|

Engraving based on the r/h figure in the

1879 engraving.

|

Arthur Bell Nicholls' first wife was Charlotte Bronte and after her

death in 1855 he remained at Haworth Parsonage until the death of her father, Rev Patrick

Bronte, in 1861. He returned to Ireland and in 1864 married his cousin, Mary Anna

Bell (1830-1915). Mary had met Charlotte a decade earlier, when she was on her honeymoon in

Ireland, but she never met Emily or Anne.

After being hidden away in a wardrobe for 50 years, the 'Profile Portrait' was

'discovered' along with the Pillar Portrait, in 1914. This was eight years the death of

Arthur Nicholls and his Mary Nicholls identified the portrait as Emily. In a

letter to Reginald Smith her niece wrote on her behalf that "the one of Emily [she]

had seen, & remembered Mr Nicholls telling [her] he had cut it out of a painting done by

Branwell as he thought it good but the others were bad, & he told Martha to destroy the

others."

The portraits were not displayed at the house in Ireland so

the identification depends on whether Mrs Nicholls correctly remembered an event on

one day some fifty years earlier. Some historians believed that she had identified the

portrait using what was then the only published portrait of

Emily, an illustration published 14 years earlier. This was an

engraving created by Smith, Elder c1900 on the advice of Clement Shorter based on

the right-hand figure in the 1879 engraving; this had been identified by Martha

Brown and Ellen Nussey as Anne.

In January 1914 Mrs Ellis Chadwick published a book, In the Footsteps

of the Brontes, which included an illustration derived from Martha Brown's photo of

the other group painting, the 'Pillar Portrait.' This was the first time it had been identified as

the portrait described in Elizabeth Gaskell's biography of Charlotte Bronte.

Mrs Nicholls died in 1916 and in 1918 Mrs Chadwick published an

article claiming that the portraits were 'discovered' by Mrs Nicholls because about

December 1913 she had sent her a prospectus for her book which included

this picture of the 'Pillar Portrait'. 7.

|

|

Identification - William

Robertson Nicoll

|

|

The 'Profile Portrait' is supposed to be the picture of Emily Bronte given

to Martha Brown and seen by William Robertson Nicoll in 1879. This is because in an

article from 1908 he described Martha's portrait of Emily as "a fine and expressive

painting." His two earlier articles he describes it as "a pencil sketch of

Emily by Charlotte." More detail is given on another page: The Lost Portrait of Emily.

|

|

Identification

- The

tracings

|

|

About the time of Clement Shorter's death Charles Simpson began

compiling a biography of Emily Bronte. He had initially thought that the 'Profile

Portrait' was of Emily but after research changed his mind and when published

(1929) the book included a brief chapter advocating that it was of Anne. He

included the photo of the illustration that Clement Shorter had shown to

Charlotte's friend, Ellen Nussey, of the photo of the engraving where she had

identified the figures.

Ellen Nussey identified the sisters L-R:

Emily, Charlotte, Anne.

In 1932, Mabel Edgerley, secretary of the Bronte Society, made the

"fortunate discovery" of three tracings. These tracings were of the figures in

the 'Gun-Group' and supported the identification of the 'Profile Portrait' as Emily. When

these tracings were discovered it was thought that John Greenwood had created them and that he had

labelled them, but he died some 70 years earlier so this was an assumption. We know that Charlotte

and her husband did not want any portraits published so it is unlikely that they let John Greenwood

loose with tracing paper and pencil, especially as he was the village stationer.

|

Tracings either created for or from the

'Gun-Group.'

These are labelled L-R: Anne, Charlotte, Emily.

|

|

Photo of the original 'Gun-Group.'

|

In the tracing of Charlotte her right shoulder is visible, as well as her

left hand. In the photo of the original portrait her shoulder isn't visible and her hand

is below the table. It is likely that the tracings were created

by Branwell and used to position the figures whilst composing the portrait in the

1830s.

|

|

Identification - Martha

Brown

|

|

Martha Brown (the Bronte’s servant) had Branwell's original

'Gun-Group' portrait photographed c1858. Her collodion photo on glass was similar to

a glass negative and a paper print was made from it in 1879; from this print an

engraving was created to illustrate a book, Haworth Past & Present by Joseph

Horsfall Turner. Martha also identified the figures in the

picture.

The engraving as published in Haworth

Past and Present.

"Our picture of the Bronte group

is a faithful reproduction of Mr. Branwell's painting of himself and sisters. I am told the

features of his sisters are represented accurately, but his own are not good. Anne is on Branwell's

left, Charlotte on the right, and Emily to the right of

Charlotte."

This is the published description which doesn't make sense and it

can't be a coincidence that it is describing an image which has been reversed.

Martha Brown will have given her description of the

painting when Horsfall Turner visited and viewed her photo on glass. This was a small, framed

collodion photo and these were normally presented as a reversed image so the description

needs to be read whilst viewing the portrait as Martha Brown would have seen it - reversed.

(see images below).

|

Photograph of the original 'Gun Group'

painting as

printed on paper from Martha Brown's

collodion photo on glass, 1879. The Profile Portrait appears on the right. The engraving was

created from this photo.

|

|

Photograph of the original 'Gun Group'

painting as Martha Brown viewed it -

as a reversed image. Because it is reversed, the 'Profile

Portrait' appears on the left.

"Anne is on Branwell's left, Charlotte on the

right, and Emily to the right of Charlotte."

|

Collodion photos are similar to the

later glass negatives and Martha's was sent to a Bradford photographer in 1879

who printed it (orientation correct) as a carte de visite (small photo on a card mount).

The engraving was made from this cdv to illustrate Horsfall Turner's book

Haworth Past and Present, published in 1879. The description in the book - buried in the text on

another page - wasn't altered to take the reversal into account. For the PDF version of the Horsfall Turner's book click here - the image is between

pages 136-7 & the description is on p.170.

|

|

Identification - Ellen

Nussey

|

|

Copies of the image below had been circulating in

Haworth since the early 1880s and in the 1890s Clement Shorter showed it to

Charlotte’s lifelong friend, Ellen Nussey. She remembered the original painting and

initialled the figures as seen below from left to right as: Emily, Charlotte, Branwell

& Anne.8.

The 'Gun-Group' illustration.

The figures were identified by Charlotte's friend, Ellen Nussey.

The Profile

Portrait relates to the figure on the far right.

Until 1989, this illustration was thought to be a

'drawing' by Branwell and the (1970s) NPG catalogue description states that

Ellen Nussey's labelling of the figures was "probably correct." This is partly because

she remembered the portrait and partly because it makes sense; Emily was the tallest and Anne

the smallest. However, the identification of the figures in this 'Gun-Group

drawing' couldn't be applied to the those in the 'Gun Group painting'

because they were considered to be two unrelated group portraits. Emily and

Anne were not necessarily seated in the same position in both portraits.

In 1989 the photograph (below) of Branwell's

original 'Gun-Group' painting was discovered and it was found that Branwell's

'drawing' was actually an 1870s engraving made from this

photograph. There was no second 'Gun-Group' portrait.

Photo of the original "Gun-Group" portrait

taken c1858 - a copy discovered in

1989.

|

|

Identification - William

Davies

|

|

William Davies visited Rev Patrick Bronte at Haworth Parsonage in 1858 and was

shown the "Gun-Group" portrait.

"On coming away we were shown a painting on the staircase of the sisters

by their brother Branwell. It was crude and harsh from a technical point of view, but the

likenesses were said to be good. The artist himself figured in the picture. He was represented

standing in the middle of the canvas with a gun resting on the ground, dividing the picture by

an awkward line. The details are not very clear to me at this length of time, but I remember

thinking that the portrait of Emily bore a resemblance to the sweet face of the figure looking

out of the picture of Millais' Autumn Leaves.” 8a.

The only figure in the "Gun-Group" definitely not looking out is the one

on right-hand side - the surviving 'Profile portrait.'

John Everett Millais' Autumn Leaves (1856),

Manchester Art Gallery, on Wikipedia

|

|

Comparison using the

tracings & 'Pillar Portrait.'

|

|

The right-hand tracing represents the

'Profile Portrait' identified as Emily since 1914.

Ellen Nussey stated that “Anne was quite different in appearance from the

others” so it should be possible to differentiate between Emily and

Anne.9. The

tracings below relate to the figures on the left and right of the 'Gun-Group,' one will be

Emily and the other Anne. One sister has a straight nose and the other an aquiline nose.

These are compared here with Emily and Anne in the only surviving group

portrait, known as the 'Pillar Portrait.' From Elizabeth Gaskell’s description of this painting

(1857) we know that the smaller sister is Anne. She has an aquiline nose; this is confirmed by

other portraits of Anne created by Charlotte and one is verified by their father.

|

|

Comparison - Emily &

George Henry Lewes

|

|

There are no other ‘identified’ portraits of Emily but a strong clue as to

her looks can be found in a letter by Charlotte concerning George Henry Lewes whose

"face almost moves me to tears—it is so wonderfully like Emily—her eyes, her features—the very

nose, the somewhat prominent mouth, the forehead—even at moments the expression." Emily didn't

look like Lewes in this photograph of him as a much older man but we can see that

his nose was not aquiline; it was straight and at a similar angle to Emily's in the 'Pillar

Portrait.' This photograph can also be compared with the 'Pillar Portrait' and the

tracings.10.

|

|

Comparison - Charlotte's

Portrait of Anne

|

|

Charlotte's portrait of her sister Anne.

|

The Profile Portrait - Emily or Anne?

|

Anne was "quite different in appearance from the

others”. Charlotte's portrait of Anne, verified by her father, resembles the sister in

the 'Profile' portrait.

|

|

Conclusion.

|

|

The NPG catalogue description for the Profile Portrait was published in the

1970s. It was thought that there had been three or four group portraits and that

the engraving, with the figures identified by Ellen Nussey, had no connection with the

'Profile Portrait.' Since 1989 it has been known that the photograph of the

original 'Gun-Group,' the tracings, the engraving of the 'Gun-Group' and

the 'Profile Portrait' all relate to Branwell's original 'Gun-Group' and

that there was only one version of it.

In the 1970s the theory was that after the 'Profile

portrait' was taken to Ireland it had returned to England, was in the

possession of Martha Brown in 1879 and then returned to Ireland, ending up in Mr

Nicholls' wardrobe alongside the 'Pillar Portrait.' If William Robertson Nicoll's two earlier

statements (see Lost Portrait of Emily) are correct, the

'Profile Portrait' was not given to Martha Brown and the portrait spent 50 years in the wardrobe

in Ireland. Robertson Nicoll's earlier statements make it clear that Martha possessed a

pencil sketch of Emily by Charlotte, not an oil painting of Emily by Branwell.

When the tracings are compared with the 'photograph of the original

Gun-Group' discovered in 1989 they match the outline of the figures, but

the tracing of Charlotte extends further to her right. It isn't known whether these tracings

predate or postdate the picture but this difference suggests that they were used by

Branwell to compose the portrait in the 1830s and that the labels were added decades

later.

The identification by two of the most reliable sources, Martha Brown and Ellen

Nussey, carry a great deal of weight. Clement Shorter's evidence from the 1890s has been

used to support identification as Emily but ultimately he changed his mind about the portrait,

believing that it depicted Anne. Mrs Nicholls identification depends upon how reliable her

memory was of a fleeting moment on one day, fifty years before.

The visual evidence is more dependable. Branwell has depicted the

right-hand figure as the smallest of the group which suggests that this is Anne. Comparison of

the tracings with Anne and Emily in the 'Pillar Portrait,' to us, makes it clear that the

right-hand tracing is Anne.

The 'Profile Portrait' is treated on this website as a portrait

of Anne; if more evidence comes to light in support of either Emily or Anne it will be added to

this page.

The 'Profile Portrait' at the National Portrait

Gallery

|

|

RETURN TO CONFUSING PORTRAITS INDEX

|

|

Footnotes

|

|

1. The Bronte Portraits: a

Mystery Solved. Juliet R. V. Barker Bronte Society Transactions The Journal of Bronte Studies,

Volume 20, Part 1, 1990 , pp. 3-11

2. Shorter, Clement K:

Charlotte Bronte and Her Circle, ed. 1896, p.123 footnote.

"After Mr. Bronte's death

Mr. Nicholls removed it to Ireland. Being of opinion that the only accurate portrait was that

of Emily, he cut this out and destroyed the remainder. The portrait of Emily was given to

Martha Brown, the servant, on one of her visits to Mr. Nicholls, and I have not been able to

trace it. There are three or four so-called portraits of Emily in existence, but they are all

repudiated by Mr. Nicholls as absolutely unlike her."

3. Mrs Nicholls stated in a

letter to the press (through a close family friend, Rev Sharrard) that the portraits had never left

the house in Ireland, probably after questioning the housemaids:

“Sir, I have received a

copy of the “Morning Post” containing an article animadverting on some information I had

recently forwarded to the King’s County Chronicle with reference to the above. I may state that

your account of the discovery, &c., of the pictures – though not quite correct- was nearer

the truth than any of the accounts I read in other newspapers. The facts are as

follows:

The pictures sent by Mrs.

Nicholls to the National Gallery have been at The Hill House, Banagher, ever since they were

brought there by the late Rev. A. B. Nicholls. The single one of Emily [?] – cut out of a large

portrait containing three sisters – was preserved by Mr. Nicholls. The rest of picture, with

the portraits of his wife Charlotte and Anne [?], was handed to Martha Brown – who lived at The

Hill House for upwards of eight years – not for preservation, but to be destroyed, and it is

believed it was destroyed by her. I need not go into all the reasons for this action on the

part of Mr. Nicholls.

You see, therefore, that I

was correct in saying that the picture of Emily forwarded to the National Gallery was never in

Martha Brown’s possession, though I was mistaken in implying that Mr. Nicholls had ever given

any portrait to Martha Brown. I have the above facts on the best living authority. Yours

&c.

James J. Sherrard., Banagher, March 8, 1914"

Page location

here (PDF - external

website).

4. The Times, Friday 7 December

1906; P.12

5. It was assumed that the

newly discovered 'Profile Portrait' was the same portrait of Emily seen by William Robertson Nicoll

in 1879 but see "Lost Portrait of Emily."

6. Clement Shorter writing in

The Sphere, Saturday 24 May 1924, p.230:

".....Mr Edmund

Gosse...praises the "unique and valuable portrait of Emily," which Mr Drinkwater in his little

book has wrongly titled, for it is really a portrait of Anne. (Here Mr Drinkwater errs, it is

true, with the National Portrait Gallery.) This is quite easy of proof."

Shorter is referring

to the 'Profile Portrait' illustrating the

frontispiece of

John Drinkwater's publication - Branwell Bronte's translation of "The Odes of Quintus Horatius

Flaccus Book 1" published in 1923.

7. THE NINETEENTH CENTURY and

After, A Monthly Review., JULY—DECEMBER 1918. August 1918 "Patrick Branwell Bronte" by Esther Alice

Chadwick. P309-10,

"Although Branwell Brontë

never attained fame as an author or artist, an oil painting of a group of his three sisters by

him hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. I had the honour of discovering that this portrait

was a genuine likeness of the three Bronte sisters by publishing in December 1913 a photograph

taken direct from the painting. On seeing this on the prospectus of my book In the Footsteps of

the Brontës, which was sent to Mrs. A. B. Nicholls (who was the cousin and second wife of

Charlotte Brontë's husband), she recognised it as a copy of the original oil painting which had

been left to her by her husband, after being stowed away in his home at Banagher, Ireland, for

nearly sixty years.

Mrs. Nicholls did not know

it was an actual likeness of the sisters painted by Branwell, and strange to say, Mr. A. B.

Nicholls was also ignorant of the fact, for when a photograph of it was submitted to him by Mr.

Clement Shorter thirty-one years ago he described it as not being genuine. He stated that the

portrait of Charlotte was that of Miss Branwell, and described the one of Emily as unlike her,

although the figure representing Anne he admitted had a slight resemblance to her. Mr. Clement

Shorter, on the authority of Mr. Nicholls, described this as a bogus portrait, in an early

number of The Woman at Home, but I was able to prove that it was genuine by comparing it with

Mrs. Gaskell's minute description published more than sixty years ago.

Mr. George Searle Phillips

also left an account of it in an article published in the Mirror in 1872, and he stated that it

was then in the possession of Charlotte Brontë's husband, which was quite correct. Moreover,

those who knew the Brontës at Haworth were certain of the genuineness, and I interviewed the

daughter of the photographer who took the photograph from the original before Mr. Nicholls

removed it to Ireland in 1861.

Branwell's painting of his

sisters does not hang in the National Portrait Gallery on account of its merit, but because it

is an authentic portrait of the three famous sisters, and contains the only genuine portrait of

Emily, except one in a photograph taken from a carbon drawing by Branwell of the three sisters

and the brother, the original of which has been lost for many years."

8. Simpson, Charles. Emily

Bronte. London: Countrylife, 1929. The illustration of the engraving with figures identified by

Ellen Nussey faces p. 204.

8a. Lemon, Charles. Early

Visitors to Haworth: From Ellen Nussey to Virginia Woolf (Keighley: Brontë Society, 1996),

p.56

9. Reminiscences of Charlotte

Brontë. Ellen Nussey. Scribner's Monthly, an illustrated magazine for the people Volume 2 Issue 1

(May 1871).

10. Letter from Charlotte

Bronte to Ellen Nussey, 12 June 1850.

“I have seen Lewes too—he

is a man with both weaknesses and sins; but unless I err greatly the foundation of his nature

is not bad—and were he almost a fiend in character—I could not feel otherwise to him than half

sadly half tenderly—a queer word the last—but I use it because the aspect of Lewes's face

almost moves me to tears—it is so wonderfully like Emily—her eyes, her features—the very nose,

the somewhat prominent mouth, the forehead—even at moments the expression: whatever Lewes does

or says I believe I cannot hate him.”

|

|

|

|

|