| |

Portraits of Emily Bronte

|

| |

|

1830s-1880s

|

|

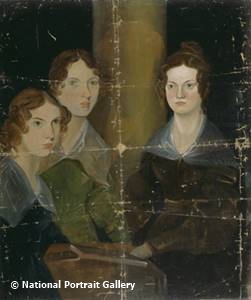

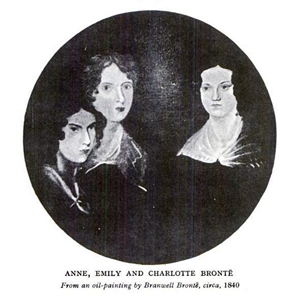

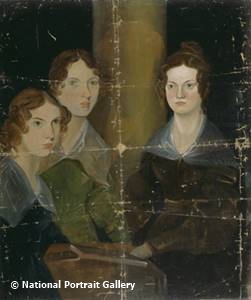

The 'Pillar' portrait.

|

The 'Profile' portrait the only surviving

figure from the Gun-Group portrait.

|

In the 1830s Branwell Bronte painted two group portraits of

his sisters, often referred to as the 'Pillar' portrait and the 'Gun' group. In the 1850s the two

paintings were at Haworth Parsonage and seen by some visitors. About 1858

a local photographer copied the two group paintings for the Bronte's servant, Martha

Brown; these were collodion photos (on glass).

After the death of Rev Patrick Bronte in 1861 Charlotte's

widower, Arthur Bell Nicholls, left Haworth for Ireland, taking the portrait paintings with him. He

destroyed the 'Gun Group' in the 1860s, apart from the right-hand figure known as the 'Profile

Portrait,' which he wrapped in paper along with the 'Pillar' portrait and stored in a

wardrobe. The only visual record of the two paintings was Martha Brown's two photographs, but these

remained stored away with her other Bronte relics.

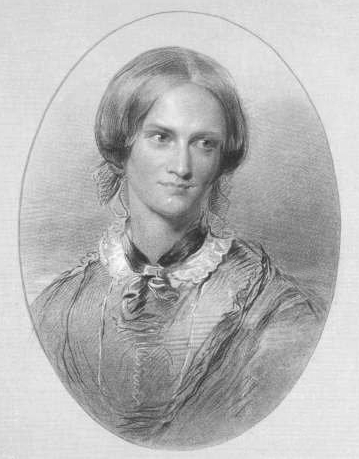

Engraving of Charlotte Bronte, published 1857.

The only portrait of the sisters to be published before the 1890s was an

engraving of Charlotte's portrait by George Richmond (published 1857) and variations based upon it.

One other image was the engraving (below) created from Martha Brown's photo of the 'Gun Group' and

published in Haworth, Past and Present (1879) but this was a local history book. Branwell

was identifiable but not the sisters, because the description, tucked away in the text on another

page, read: "Anne is on Branwell's left, Charlotte on the right, and Emily to the right of

Charlotte" which did not make sense.

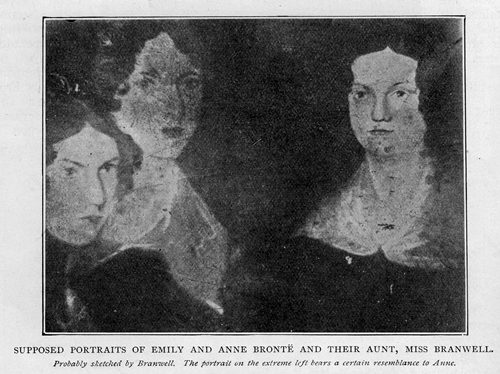

'Bronte Group' also known as the 'Gun-Group' published

1879.

The history of the two 1830s group portraits and Martha Brown's

two 1850s photographs is known about today, but historians only started to research

them in the 1890s, when little or nothing was known. The only mention of a group

portrait was in Elizabeth Gaskell's biography of Charlotte Bronte (1857) but the painting had

vanished. Copies of the 'Gun-Group' engraving existed but it was not known what it was,

where it had come from or whether it was genuine. When the description in Haworth,

Past and Present was found, it did not make sense. Over the next century the

pieces of the 'portraits puzzle' were gradually put together, but not always in

the correct place.

|

|

1890s

|

|

After the Bronte Society was founded In 1893 preparations were made for the

first museum. Portraits of the sisters were sought so they could be copied for display in

the museum and to illustrate future publications. At this time, the 1857 engraving of

Charlotte existed as well as a beautiful painting created from the engraving by John Hunter

Thompson. For Anne, there was the pencil portrait of her by Charlotte, purchased from Martha Brown

by William Robertson Nicoll back in 1879. There were no portraits of Emily Bronte and

historians launched a crusade to find one.

The Bronte Museum opened in 1895 above the Yorkshire Penny

Bank.

William Walsh Yates, editor of the Dewsbury Reporter, travelled to Blackpool to

visit Robinson Brown, a cousin of the Bronte's servant, Martha Brown (d.1880) with a large

collection of Bronte memorabilia. Yates was told that "a photograph of her on

glass" had existed but had been accidentally "broken to

atoms." The earliest photos on glass date from the 1850s, so this must have been a copy

of an earlier image. If it was not a copy of an actual photograph then this was probably

Martha Brown's 1850s photo of Branwell's 'Gun Group' painting1.

|

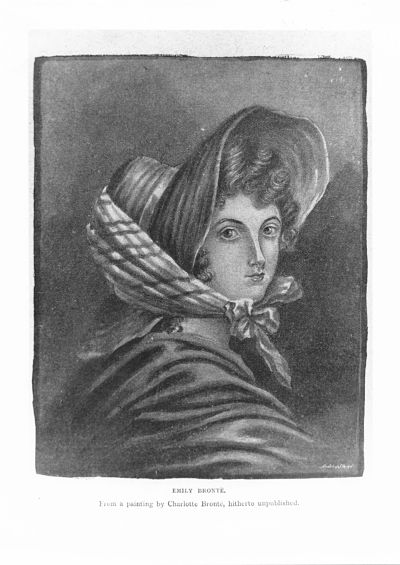

Portrait of Emily Bronte, published

in an article by Frederika MacDonald (1894).

|

About the same time, a picture "Emily Bronte. From a painting by Charlotte

hitherto unpublished" appeared in an article in Woman at Home in 1894.

There was no mention as to where it had come. It may have been inserted by the contributor,

Frederika MacDonald, or the owner of the publication, William Robertson Nicoll.2

Joseph Horsfall Turner travelled to Ireland to visit Charlotte's widower, Arthur

Bell Nicholls, but he gleaned very little about the portraits. Clement Shorter also

visited Arthur Nicholls and raised the subject of the missing group 'Pillar' portrait,

described by Elizabeth Gaskell in 1857. Shorter was left with the impression that there had only

been one group portrait and that it had been destroyed, apart from the figure of Emily, which had

been given to Martha Brown.3.

In 1897 Shorter sent Arthur Nicholls a print from a photo of a

painting which had once belonged to Martha Brown.' Arthur Nicholls replied in March 1897 that

"The photograph you enclosed does bear a resemblance to the picture of the three sisters - it

is just possible that Martha Brown had it copied before we left Haworth - The likenesses are very

bad - The head in the left hand corner has something of the expression of Anne - The others I

should not recognise."

Shorter was given the impression that no images

of Charlotte existed, other than her

portrait by George Richmond, first published in 1857.

It was of course a photo of the 'Pillar Portrait' (L-R: Anne, Emily,

Charlotte), as described by Mrs Gaskell in her biography of Charlotte, (1857), but Clement Shorter

did not know this. Arthur Nicholls avoided naming Charlotte in this portrait probably because

Elizabeth Gaskell had stated in 1857 that it bore a striking resemblance to her. This portrait

by Branwell obviously bears little resemblance to her portrait by George Richmond, authorised

for publication by Arthur Nicholls in 1856. Clement Shorter published the image in

Woman at Home (1897) with an ambiguous and incorrect description and subtitle (as

seen above).

Just to muddy the waters, several portraits of Emily emerged from

various parts of Yorkshire, all purporting to be of the author, but all of very different

women. Frustrated historians abandoned their search for a genuine portrait and from this date

portraits of Emily and Anne began to be confused.

|

Emily Bronte, artwork published by

William Scruton, 1898. This is derived from the figure of Anne in the 'Pillar

Portrait.'

|

Emily Bronte, engraved for Smith,

Elder, 1900 on the advice of Clement Shorter. This is based on the r/h figure in

the 'Bronte Group' illustration first published in Haworth, Past & Present,

1879.

|

Two pieces of artwork were created in the late 1890s, based on what were thought

to be pictures of Emily. William Scruton's portrait was copied from the left hand figure in the

photograph in Woman at Home, the identification was presumably based on the title.

The second portrait was an engraving, created by the publishers Smith,

Elder c1900 on the authority of Clement Shorter. It was copied from the right hand figure

in the 'Gun Group' because about 1899 Clement Shorter was told that the 'Gun Group' was actually a

photograph of a picture by Branwell. There does not appear to be any logic to what happened next

but for some reason Shorter took the right-hand figure to be Emily, even though Ellen

Nussey had initialled this figure as Anne.

The 'Gun Group' - Ellen Nussey identified the sisters

L-R: Emily, Charlotte,

Anne.

There were now three portraits of Emily being published, one with no provenance

and two copied, unwittingly, from portraits of Anne Bronte.

|

|

1900-1919

|

|

The three portraits commonly

used as illustrations of Emily

in books. journals and newspapers from the 1890s to the present day.

Charlotte's widower, Arthur Bell Nicholls, died in December 1906 and the

following year George Richmond's original portrait of Charlotte passed to the NPG.

It was displayed alongside another portrait of Charlotte (NPG 1444 Unknown woman, formerly known as Charlotte Brontë).

This was dated 1850 and supposedly painted by her tutor in Brussels as it was signed

'Paul Heger', even though his name was Constantin Heger. It was purchased by the NPG

earlier in 1906 and was the subject of a dispute between the gallery director, Lionel

Cust, who had agreed the purchase, and Clement Shorter, who considered it to be

fraudulent.

In October 1913 the historian, Esther Alice Chadwick, persuaded the new director

of the NPG that the portrait was not painted by either Constantin Heger or his son Paul (who

was a young boy in 1850) and it was later removed from the gallery. The exposure of the painting as

a hoax was related a few months later in Mrs Chadwick's book In the Footsteps of the

Brontes (1914).

The book also included an illustration of the long lost 'Pillar'

portrait. Esther Chadwick's stated intention in 1913 was to raise public

awareness so that the painting, not seen for over 50 years, might be found. This was the

first time that the portrait had been published in a book and the first time the sisters had

been correctly identified.

The illustration of Branwell's 1830s 'Pillar' portrait used in Esther

Chadwick's book, of the long lost Pillar portrait.

It was copied from the late Martha Brown's 1850s glass photo.

The book was published in January 1914. Two months later newspapers reported a

miraculous discovery. Eight years after the death of Arthur Bell Nicholls the 'Pillar Portrait' and

'Profile Portrait' had been 'discovered' by his widow, his second wife, at the house in Ireland.

They had been hidden away for over 50 years. The discovery must have come as a great shock

for Clement Shorter. He had visited and corresponded with Arthur Bell Nicholls for nearly a decade

and the subject of portraits had been raised several times; the paintings had been in the

house all the time.

|

|

|

|

The 'Pillar' & 'Profile'

portraits discovered in 1914.

|

The two paintings were purchased by the National Portrait Gallery amid

international press coverage about their romantic discovery. Any embarrassment caused by

Esther Chadwick's exposure of the 1906 'hoax portrait of Charlotte Bronte' (NPG 1444) in her book was forgotten. Weeks later though another row erupted

with the potential for further embarrassment and scandal.

Esther Chadwick now challenged the identity of the 'Profile Portrait' as Emily,

believing that this could only be Anne. She knew that Mrs Nicholls had never met Emily or

Anne and had probably identified them from the illustration in a book prospectus she

had sent to her late 1913. She also knew that Clement Shorter had made an error in publishing the

right-hand 'Gun-Group' figure as Emily in 1900, and thought that Mrs Nicholl's had identified the

'Profile' portrait from this. Above all, she knew that Emily did not resemble Anne. If this

surviving 'Profile' by Branwell was Emily then she should not resemble Charlotte's pencil portrait

of Anne in the slightest.

|

Above: Anne Bronte

by Charlotte. Right: The 'Profile' portrait by

Branwell.

|

|

A second problem then surfaced because this was supposed to be the portrait of

Emily, owned by Martha Brown, and seen by William Robertson Nicoll when he visited her in 1879.

Over in Ireland, Rev Sherrard, a close friend of the late Arthur Nicholls, wrote to the Morning

Post on behalf of Mrs Nicholls. He claimed that the portrait was never in the possession of

Martha Brown and it had not left the house in Ireland.

William Robertson Nicoll seems to have remained silent on the matter and it was

all brushed under the carpet. The NPG was partly occupied with suffragette attacks and by August

1914 the country was at war. Mrs Nicholls died in 1916 and in 1918 Esther Alice Chadwick published

an article claiming that the portraits were 'discovered' by Mrs Nicholls because late

in 1913 she was sent a prospectus for her book, which included the picture of the 'Pillar

Portrait.'

|

|

1920s

|

|

In 1914 Clement Shorter believed that the 'Profile' portrait was

Emily but by the 1920s he had changed his mind, deciding that it "Is really a

portrait of Anne." He died in 1927, just as Charles Simpson began researching his

book Emily Bronte (1929). Simpson initially considered the 'Profile Portrait' to be Emily

but changed his mind during research. In his book he included a brief chapter on the subject.

Included was an illustration, the photo (below) of the engraving where Ellen Nussey had identified

the figures. The 'Profile Portrait' resembled the right-hand figure, labelled as Anne.

Ellen Nussey identified the sisters

L-R: Emily, Charlotte,

Anne.

|

|

1930s

|

|

In 1932, three years after Charles Simpson's book was published, an article

"Emily Bronte - A National Portrait Vindicated" was published in

The Yorkshire Post by the secretary of the Bronte Society, Mabel Edgerley. She

announced "a fortunate discovery which has important bearing on the authenticity of a portrait

believed be that of Emily Bronte."

The "fortunate discovery" was three tracings labelled with the

sisters' names and ages. These were said to have been traced c1860 by John Greenwood, the Haworth

stationer, from the mostly destroyed 'Gun Group' portrait, before it was taken to

Ireland. A copy of the tracing labelled "Emily Jane Bronte" was made, taken to the

NPG, placed over the 'Profile Portrait' and found to be a close match. As the tracing was

labelled Emily it was decided that the NPG attribution was correct.

Unfortunately, the left-hand tracing was ignored. Once it had been established

that the tracings were from the lost portrait they should have been compared against the figures of

Emily and Anne in the 'Pillar' portrait where the identities are undisputed. Emily

and Anne were "quite different in appearance" and just looking at the shape of

the nose would have proved that the 'Profile' portrait was Anne.

|

The tracings identified the sisters

L-R:

Anne, Charlotte, Emily.

|

|

Ellen Nussey identified the sisters

L-R:

Emily, Charlotte, Anne.

|

The labels on the tracings contradicted Ellen Nussey's identification in the

engraving where the figure on the right was Anne. It was decided that Ellen Nussey may have been

correct but the image (now known to be an engraving), was thought at the time to be a drawing by

Branwell and considered to be a completely different group portrait. This was partly due to

differences in clothing and the wallpaper.

The labelling of the tracings did not convince everyone but there was

no Esther Chadwick to challenge the way the evidence had been interpreted. Virginia Moore

then devoted a page in The Life and Eager Death of Emily Bronte (1936) giving reasons

why she thought the portrait was of Emily, in part because "it deserves to be

Emily".4.

|

|

1950s -

1970s

|

|

In 1958 the debate resurfaced when Ingeborg Nixon published a very

balanced article about the two NPG portraits in the Bronte Society

Transactions.5.

There was a

response by Dame Myra Curtis (1959) questioning amongst other

things, resemblances and the labelling of the tracings.

In The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë (1960) Daphne du

Maurier touched on the portrait but all she had to say on the subject was that

"Sentiment and tradition give this lovely profile to Emily, but the

resemblance to the figure of Anne in the [Pillar Portrait] group would suggest

otherwise."

The NPG catalogue description was published in the 1970s and

addressed the identity question, concluding that it is Emily although there were certain

reservations. Since publication other evidence has emerged.

|

|

1980s

onwards

|

|

In 1989 a photograph of the original 'Gun Group' portrait was discovered and a

number of mysteries were solved, enabling the number of contradictory and complicated arguments to

be reduced. What was thought to be a drawing by Branwell of an

unrelated 'Gun Group' was actually an engraving made in 1879 using the newly discovered

photo. The differences, such as the wallpaper and clothing, could be put down to artistic

license because the photo was dark and lacked detail.6.

The newly discovered 'photo,' the

'engraving,' the 'tracings' and the 'Profile Portrait' all

related to Branwell's original 'Gun-Group.' It had been thought that there were three

or four group portraits but it was now known that there had only ever been two - the 'Pillar

Portrait' and the "Gun Group.'

|

Tracings from the "Gun Group" made either c1835 or

c1860. The sisters are identified

L-R:

Anne, Charlotte, Emily.

|

The "Profile Portrait" at the NPG.

|

|

Copy of a photo taken c1858 but

not discovered until 1989, after publication of the NPG catalogue description.

This is the original "Gun-Group" Portrait with "Profile Portrait" on the far right.

|

An engraving made from the photo and published in Haworth Past and Present, 1879. The

figures were identified by Martha Brown, but are on another

page.

|

|

A photo of the engraving with the

figures identified by Ellen Nussey as

L-R: Emily, Charlotte, Anne.

|

A number of questions remain unanswered. Ellen Nussey's

identification of the figures in the engraving still conflicts with the labels on the

tracings. Were the tracings made by Greenwood in the 1860s or created by Branwell in the

1830s? Branwell did use "mechanical devices" in the 1830s as an aid to drawing so the

'tracings' were perhaps 'drawings' created using a Camera Lucida. 7.

Two earlier accounts of William Robertson Nicoll's visit to Martha Brown state

that her portrait of Emily was a pencil sketch by Charlotte and not an oil painting by

Branwell. Then there is Martha Brown's confusing identification of the figures in the

'Gun Group' in Haworth Past and Present. Some of these questions are explored on the

next page.

---

All of this contradictory evidence has muddied the waters and historians

have not always been objective in the matter so it is best to return to the original sources.

Branwell's group portraits, however bad, were considered by the family to be good likenesses of the

sisters. Emily and Anne were not twins, Anne had a Roman nose and Emily did not. All that

is required to resolve the identity of the 'Profile' portrait is to compare the

figure with the known portraits and contemporary descriptions of Emily and Anne.

The only undisputed portrait of Emily Bronte.

|

|

RETURN TO CONFUSING

PORTRAITS INDEX

|

|

Footnotes

|

|

1. W. W. Yates, "Some Relics of the Brontes", The

New Review (1894) pp. 482, 486 "The Brown collection once boasted a memorial of Emily Brontë of great

interest and value—a photograph of her on glass, I am informed, and described to me as a

negative. Not one so called nowadays. It was entrusted to a Bradford gentleman to be copied,

but he unfortunately fell, and the relic, to his great regret and that of its owner, was

broken to atoms. Brontë-lovers all the world over are much the poorer through that

accident."

2. Joseph Horsfall Turner travelled to Ireland to visit Charlotte's

widower, Arthur Bell Nicholls, and was told that the portrait in Woman at Home was unlikely to

be of Emily. see Yorkshire

Post and Leeds Intelligencer, Wednesday 12 September

1894. The full quote from the newspaper is:

"Of the portrait of Emily Bronte in the July number of the

Woman at Home he [Mr Nicholls] observed that it might be genuine, but that it did not accord,

either as to the head-dress or as to the features, with his recollection of

her."

The portrait in The Woman at

Home, July 1894, was also published Clement Shorter

as "Emily Bronte, from a portrait

drawn by Charlotte" in an article,

Mrs. Gaskell and Charlotte Bronte, in The Bookman, June 1896, pp. 313-323

Clement Shorter wrote in 1900

that it "was afterwards admitted to have been a fashion

plate." . The picture does

not resemble fashion plates produced in the C19th so where the picture came from, and the identity

of the woman, remains a mystery. There were several 'portraits of Emily Bronte'

existing at the time, all of different women, so it may have been one of

these.

3. Clement King

Shorter, Charlotte Brontë and her Circle (London, 1896) pp.123-4. "After Mr. Bronte's death Mr.

Nicholls removed it to Ireland. Being of opinion that the only accurate portrait was that of Emily,

he cut this out and destroyed the remainder. The portrait of Emily was given to Martha Brown, the

servant, on one of her visits to Mr. Nicholls, and I have not been able to trace it. There are

three or four so-called portraits of Emily in existence, but they are all repudiated by Mr.

Nicholls as absolutely unlike her. The supposed portrait which appeared in The Woman at Home for

July 1894 is now known to have been merely an illustration from a 'Book of Beauty,' and entirely

spurious."

By 1924 Clement Shorter believed

that the "Profile" portrait at the NPG was of Anne.

The Sphere - Saturday 27 January 1900.

"It has long been an axiom

among Bronte enthusiasts that no portrait of Emily Bronte is in existence. It would appear,

however, that a photograph which always is on sale at Haworth, and has been reproduced in several

magazines and books, of a group purporting to be the Bronte family is really a photograph of an

actual picture by Branwell. Mr. Nicholls, the

husband of Charlotte Bronte, who still lives in Ireland and who takes the keenest possible interest

in the fortunes of The Sphere has identified the photograph. He says that the likeness of Emily is

excellent, whereas the portraits of his wife, of Anne, and of Branwell Bronte, are quite

worthless. On the strength of this

identification, Messrs. Smith and Elder are producing a beautiful photogravure of the portrait of

Emily Bronte, which will be published next month in the new edition of "Wuthering Heights" with

Mrs. Humphry Ward's introduction."

4. Virginia Moore, The Life and Eager Death of

Emily Brontë. London: Rich & Cowan, 1936. NOTE ON THE PORTRAIT OF EMILY BRONTE,

p369.

"if the

soul, as I believe, forms its own body, this single [Profile] portrait, alone among the portraits of the Bronte sisters, deserves to be

Emily, for here only, through Branwell's inexpertness, shines the power and poetry which were

her inalienable characteristics."

5.The Bronte Portraits - Some Old Problems and a

New Discovery By Ingeborg Nixon, M.A., PH.D. Bronte Society Transactions The Journal of Bronte

Studies, Volume 13, Part 68, 1958 , pp. 232-238

5a. The "Profile" Portrait, Dame Myra Curtis.

Bronte Society Transactions The Journal of Bronte Studies, Volume 13, Part 69, 1959 , pp.

342-346

6. The Bronte Portraits: a Mystery Solved. Juliet

R. V. Barker Bronte Society Transactions The Journal of Bronte Studies, Volume 20, Part 1, 1990 ,

pp. 3-11

7. Art of the Brontes p.27

|

|

|