| |

Hats & Cloaks

|

|

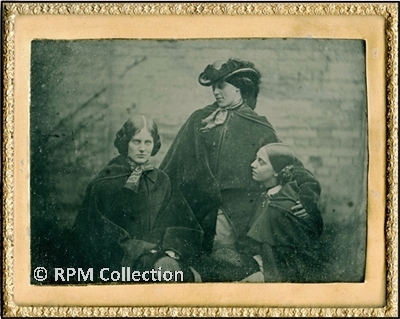

The suggestion that the photograph could be a portrait of the Bronte

sisters has been criticised mainly because of the hats, or rather the hat worn by

'Emily', because it does appear to date to the 1860s and not to the 1840s. This page

traces the origins of the hat in Britain.

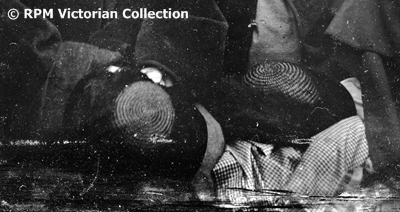

The straw hats held by 'Charlotte' and 'Anne' (above) are partly obscured so it

is not possible to tell whether they are exactly the same style as the one worn by 'Emily'

(below). This has a round, low-crown with the brim turned up at the sides and is

similar if not identical to a riding hat seen in photographs from the early

1860s. If the hat dates from the 1860s then these are certainly not the Bronte

sisters because Emily died in 1848 and Anne in 1849.

The hat worn by 'Emily' in the photo.

When was this hat introduced to Britain and Is there any evidence

that it existed in the 1840s?

|

|

Women's hats in the

1840s

|

|

Bonnets - detail from a fashion plate in Le Follet, August,

1845.

In the 19th Century, women's fashions in Britain were strongly

influenced by a mixture of propriety and Parisian fashions and this ensured

that the bonnet remained the main outdoor headwear throughout the 1840s and

1850s. By the late 1830s hats had been demoted in status

to informal headwear and they rarely merited an appearance in

fashion journals until the late 1850s.

Wide-brimmed straw hat; detail from a fashion plate in Le Moniteur de

la Mode, July 1844.

Women's hats did not disappear altogether in the 1840s. Milliners throughout the

country continued to sell them in addition to bonnets. They were worn in the garden, at the seaside

and in the country, away from larger towns and cities where dress codes were more

relaxed. They were usually made of straw and most had a wide, floppy brim.

A satirical sketch of the floppy, wide-brimmed English straw hats worn

in the countryside in the 1840s.

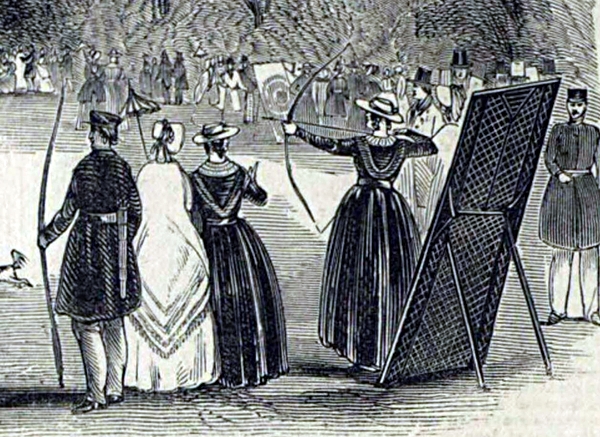

For wealthier women with an interest in sports, archery was about the only

option available in the 1840s. Illustrations from this period show that whilst bonnets

were often worn, others chose to wear the wide-brimmed hats.

Detail from an engraving of an archery meeting, Pradoe, Oswestry, Shropshire, 1844. Women did not participate in many sports in the 1840s apart from archery, which

was extremely popular and where either bonnets or hats were acceptable headwear. The National

Archery Meeting was held in York in 1844.

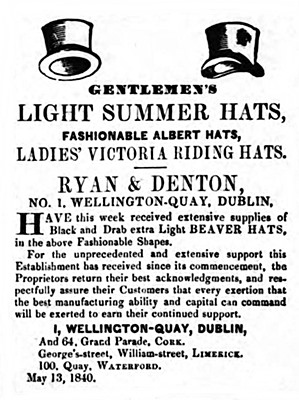

After walking, the most common outdoor leisure pursuit for many women

was horse-riding and some found riding hats more practical than bonnets. Royalty

also influenced Victorian fashion, just as it does today, and the styles

worn by the young Queen Victoria in the 1840s were copied and sold by milliners throughout the

country.

Advert for men's Albert Hats and ladies' Victoria Riding Hats, Ryan

& Denton of Dublin, Cork, Limerick & Waterford, 1840.

The main outdoor headwear for women in 1840s Britain was

bonnets with informal headwear consisting mainly of floppy rustic straw hats and stiff,

formal, riding hats, with one notable exception.

|

|

The Jenny Lind Hat

|

|

Jenny Lind

(1820-87)

|

The only radically different woman's hat to appear in

1840s Britain was known as a 'Jenny Lind', named after the Swedish opera

singer who caused a sensation when she came to this country in 1847. Existing hats

for women in the 1840s were limited mainly to the informal wide-brimmed

straw variety, or the formal riding hat style. The 'Jenny Lind' was

a complete departure from these modes. 1.

It was virtually identical to a man's 'wide-awake' hat,

low-crowned with the brim sweeping up at the sides. The hat does not appear to have

been the product of a Parisian fashion house, nor was it promoted by Jenny

Lind.

It emerged out of the 'Jenny Lind Fever' or 'Lindmania' which

swept through the country in the late 1840s. The adulation of Jenny Lind by

the British (and later the American) public can only be likened to the

Beatlemania of the 1960s.

|

|

The hat used by Jenny Lind in Donizetti's opera

'La figlia di Reggimento'.

Source: Wikimedia Commons 'Jenny Lind Fille du

Regiment'

This style of hat did not exist in Britain until 1847.

The hat was based on the one worn

by Jenny Lind in the opera 'La figlia del Reggimento' (The Daughter of the

Regiment) where she played the role of Maria, a French vivandière. This was a replica of the vivandière or

cantinière hat worn by women in certain regiments of the French Army.

The hat worn by 'Emily' in the

photo.

|

MATERIALS

The hat was produced in felt, but the straw version seems to have

been more popular. These were sold in Britain from 1847 until about 1863 including

smaller hats produced for boys & girls. Adverts also exist in this period for the 'Jenny

Lind Riding Hat' which may have been promoting the same hat or

perhaps some modified type with a narrower brim.

DISTRIBUTION, EXPORT & THE AMERICAN VERSION

They probably first became popular in the West End of London in May 1847 but

within weeks the hats were on sale in other parts of the country. They could certainly be found in

the towns and cities visited by Jenny Lind during her tours of Britain. In the run up

to her arrival the local shops stocked up on all 'Jenny Lind' memorabilia, such as mantles,

handkerchieves, boas, hats, pictures, snuff boxes and sheet music etc.,.

Advert for Jenny Lind Hats, June, 1847: George Burrington, Hatter, 81

Fore Street, Exeter, Devon.

'Jenny Lind hats' were shipped out, along with other headwear, to milliners in

other parts of the world. They were being sold in shops in Tasmania by

January 1848. Tuscan and Dunstable straw versions arrived in Sydney, Australia by

September 1848. They were also exported to America and by March 1848 they were on sale in

Louisville, Kentucky, some two years before Jenny Lind arrived in the United States.

Jenny Lind toured America with P.T. Barnum in 1850-2 and the New York hatter, John Nicholas Genin, promoted his own 'Jenny Lind Riding Hat'

which was immensely successful. Descriptions of this American version vary enormously so an

example cannot yet be given.

'POPULAR' BUT 'UNFASHIONABLE'?

In 1847 the hat was probably considered by most people in Britain to

be 'popular' rather than 'fashionable'. It was not designed by a

Parisian milliner and women's hats were still considered to be very informal

headwear. The first 'known' illustration of it in a fashion journal is in 1856, as a straw

riding hat. It was exactly the same hat, so it was probably sold by some

British milliners as a rustic riding hat, but others continued to

advertise it as the 'Jenny Lind'.

One of the last adverts found in a British newspaper for a 'Jenny Lind'

hat is in 1854, when hats were becoming more socially acceptable, new styles

were emerging. This style of hat went out of fashion about 1863 and the gradual demise of the

bonnet began.

|

|

The Jenny Lind Hat in the 1840s & 1850s

|

|

The hat worn by 'Emily' in the

photo.

The hat worn by

'Emily' in the photo can be seen in photos dating to the early 1860s, but these are

usually carte de visite photos which were only produced from about 1860. It can also be

seen in collodion photographs, which existed from the 1850s until the 1890s, but

these are mostly undateable. Fortunately the hat does occasionally appear in illustrated

newspapers and journals throughout the

1850s.

|

1847

|

|

Depictions of Jenny Lind

as Maria in La figlia del Reggimento 1847-9.

These images are taken from engravings of Jenny Lind as she

appeared in the opera The Daughter of the Regiment. In June 1847 Queen

Victoria, one of Jenny Lind's greatest admirers, made a small pencil sketch

and watercolour of her in her vivandière hat and costume. These can be seen on

the Royal Trust website (RCIN 980011.ad & RCIN 980011.ai)

|

"A CHOICE VARIETY OF THE NEW JENNY

LIND HATS, TRIMMED AND

PLAIN"

Advert for Mrs E. Pratt, Milliner, 16, High

Street, Wolverhampton (Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire

Advertiser - Wednesday 28 July 1847 p.2) 1a.

|

Jenny Lind hats were smaller than the wide-brimmed

hats worn by adults and children. 2.

|

"The polka-craze was certainly big in Paris,

two or three years ago, but it is nothing compared to the result of

the prima donna's songs which fashion has taken under its wing. In

Paris we had polka clothes and that's all; in London, all fashions

are Jenny Lind. Jenny Lind Dress, Jenny Lind Hat, Jenny Lind

collars, Jenny Lind Tobacco Pouch.

"Le charivari (Paris, France) 28 August 1847

(col.3) 3.

|

|

"R. Bissington

respectfully invites the Attention of Ladies to these

Goods in all the Newest Designs of the Season, embracing the

PALAIS ROYAL, JENNY LIND, CLARENCE, PRINCE EDWARD,

&c."

Richard Bissington, 34, Briggate,

Leeds & 16, Market Place, Hull.

(Leeds Mercury, Yorkshire, Saturday 6

November 1847)

|

|

|

c1848

|

|

A Royal Staffordshire figure of Jenny Lind produced

1847-9.

Even before she arrived in Britain, pictures of Jenny Lind

were on sale, mostly engravings made from portrait paintings. Some of these

graced the covers of sheet music, including The Daughter of the

Regiment where she wears the vivandière hat. The Royal Staffordshire figures produced c1847-9 were at

least partly based on these portraits.

|

|

1849

|

|

Before 1850s dress reform &

Bloomerism.

Women's cricket was

something of a novelty in the 1840s but in one of these rare events

in 1849 these Hampshire ladies were not wearing floppy straw hats or

bonnets:

"On Thursday week,

the return cricket match between the Ringwood [Hampshire] married and single

females took place at Picket Post, and from the fineness of the day immense

numbers attended. The ladies were dressed in white, wearing Jenny

Lind hats, the single displaying pink sashes, and the married blue.

The manner which many of them handled the bat and ball proved that they

had not been remiss in practice, and had received tuition from one well

skilled in the noble game. At the close of the game, the single were again

declared victorious, with 5 wickets to spare."

(Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette -

Thursday 20 September 1849).

|

|

1850

|

|

s.JPG)

Detail of wide-awake riding hat

from an illustration in Punch magazine. vol 18, p.236

(1850)

|

Detail of wide-awake riding

hat from an illustration in

Punch magazine, vol.19-p.25 (1850)....John Leech was very aware of changes in women's fashions and

created many of the illustrations seen in Punch Magazine.

|

|

1851

|

|

National Archery Meeting, Leamington, Warwickshire, 1851 showing

various types of headwear including one Jenny Lind or wide-awake style hat, several

wide-brimmed hats with high & low crowns, a child with a floppy straw hat

and many bonnets.

Detail

from an image in the Illustrated London News - Saturday 5 July

1851.

|

"Ladies'

Fashionable Rustic Riding Hats, as generally worn at the West End

of

London."

Richard Bissington, London Hatter, 34, Briggate,

Leeds & 16, Market Place, Hull.

Leeds Times, Saturday 19 July 1851.

|

|

|

1853

|

|

Left: Copy of a pencil sketch of Jenny Lind as Maria,

1847.

Right: Detail of wide-awake riding hat from an engraving in

Punch magazine, June, 1853.

|

|

1854

|

|

"R.

Bissington respectfully solicits Attention to the newest Designs in

SILK BEAVER and FELT HATS and BONNETS. The NEW JENNY LIND HAT is

the most

prevailing."

Richard Bissington, London Hatter, 34, Briggate,

Leeds & 16, Market Place, Hull

(Leeds Intelligencer, Yorkshire, Saturday 28 October

1854)

------

Millinery, Bonnet and Fancy Drapery

Establishment,

Opposite the Guildhall, Exeter.

Mrs C. ADAMS

HAS JUST RECEIVED A LARGE ASSORTMENT OF CRINOLINE, MILLINERY, AND

FANCY STRAW BONNETS:

Also, a New Stock of

YOUNG LADIES AND GENTLEMAN'S LEGHORN, TUSCAN, AND, STRAW HATS,

including the fashionable "Jenny Lind"

Shape,

And of which she respectfully solicits an early inspection.

58, High-street, June 15th, 1854.

(Western Times, Exeter, Devon - Saturday 17 June 1854

p.4)

|

|

|

1855

|

|

In the Copdock Archery Club's Fete,

at The Chauntry, Suffolk, on 22 August 1855, the ladies wore:

"a green silk jacket,

white muslin skirt flounced, and grey felt Jenny Lind hat,

bound at the edges with green ribbon, and set off with a white or green

feather."

Essex Standard - Friday 31 August

1855.

|

|

1856

|

|

Changes in fashion were not unconnected to the alliance between

Britain and France in the Crimean War.

Earliest known appearance of the hat in a fashion

plate: Journal des Demoiselles, 1856, p.126-8.

|

|

ABOVE: Detail from a photo of Princesses Helena and Louise © Royal

Photographic Society.

|

|

|

LEFT: Princess

Helena © Royal-Collection-Trust. The photos (above and left) were taken in

1856 by the Lancashire-born photographer, Roger Fenton. The previous year he had

spent three months making a photographic record of the Crimean War.

BELOW: The hat worn by 'Emily'.

|

|

1857

|

|

The English Hat in Paris.—The fashion set by

English ladies of wearing hats instead of bonnets has, after being a good deal

ridiculed, been adopted by actresses and lorettes. It is always those two classes

of the community who experimentalise new fashions, especially those of an eccentric

character.

There are indications that from them the new mode will soon

reach ladies of respectability, and that it will in time become general. It is said

that the Princess Mathilde has adopted it, but that the Empress has pronounced

against it. As, however, Her Majesty in her shooting excursions at Compiegne and

Fontainebleau figures in a hat, and as it became her remarkably well, it is

probable that her pronunciamento against the new fashion is not final and

irrevocable. (BEADS FROM THE BRACELET OF FASHION) Cheltenham Looker-On - Saturday

03 January 1857)

|

The riding hat seen in photos of the early 1860s is a 'Jenny

Lind Hat' in all but name. It can be traced back to London in 1847, was the

only 'wide-awake' hat for women in the whole of this period, and the

style remained popular for over 15 years.

The elegant form of the hat with a graceful, sweeping, brim was

only part of its appeal, for some women it was far more practical than a

bonnet, but there was also the connection to Jenny Lind. Most of the nation,

including the majority of the British Press, held her in high esteem; she

was a philanthropist and one of the few female role models of the 1840s. Her success in Britain,

the 'Jenny Lind Fever' and the popularity of the 'Jenny Lind' hat, were all events taking place in

1847, just as the three Bronte sisters' ground-breaking novels were accepted for

publication.

The 'Jenny Lind' hats, and what might today be termed 'Jenny Lind

unofficial merchandise', was more common in towns she visited during her tours of

1847-9. In 1847 she performed in Hull. Her concert at York was cancelled at the last

minute, but crowds did catch a glimpse of her at York Railway Station. Another concert in

Sheffield the following week was also cancelled.

|

|

Did the Bronte sisters

ever wear hats?

|

|

The sisters would have worn bonnets in the 1840s but there is mention of them

wearing hats:

"Eh, dear, when I think about them I can see them as plain to my mind's eye as if they

were here. They wore light-coloured dresses all print, and they were all dressed alike until

they gate into young women. I don't know that I ever saw them in owt but print. I've heard it

said they were pinched [short of money] but it was nice print: plain with long sleeves

and high neck and tippets down to the waist. The tippets were marrow to their dresses and

they'd light-coloured hats on. They looked grand.

If my memory serves me correctly, I believe the Miss Brontes' dresses have been

criticised by others as being somewhat quaint and prim and old-fashioned and indeed anything

but 'grand,' but then these critics had not lived in Haworth all their lives and brought up a

family on twelve shillings a week hard-earned in a mill as had my old lady."

4.

Descriptions of headwear in the Victorian era can be very deceptive because the

terms "hat" and "bonnet" were, depending on the writer,

interchangeable. Did this lady think that the Bronte sisters "looked

grand" wearing "light-coloured hats" or wearing "light-coloured

bonnets"?

|

|

The Cloaks

|

|

The three women in the photo are wearing

hooded cloaks. 'Charlotte' and 'Emily' have thick fleece travelling cloaks with sleeves

but 'Anne' is wearing a cloak made of a thinner fabric. It has been suggested that this

may be because Charlotte and Emily travelled to Belgium in

February 1842 whilst Anne remained in Yorkshire, working for the Robinson family.

|

|

|

|

Any missing sources will be added towards the end of November 2018.

There is more information concerning the hats and so this page will probably be revised

at some point in 2019.

|

|

The Yorkshire

Vivandière

|

|

Just as a note of interest, in the 1850s & 1860s volunteers rifle corps were formed in most towns in Britain. The

Leeds Engineer Volunteer Corps was probably unique in

having in its ranks, a Vivandière. When the rifle corps paraded through the

centre of Leeds they were led by a woman wearing the costume of a French

vivandière. 5.

The Vivandière of the Leeds

Engineer Volunteer Corps, 1865.

|

|

1. The English dialect dictionary, George

Wright, 1903. Volume 4, p.358 Entry for 'Jenny Lind'

(Yorkshire & London).

Brighton Gazette - Thursday 30 April 1857 col.5

"HER MAJESTY'S THEATRE" [London] "....La Figlia del Reggimento was presented for the first

appearances this season.. Mdlle. Piccolomini looked more piquant and charming than ever. The

dress of the vivandiere suits her to admiration, and then she has laid aside the

Jenny Lind wide-awake — not to speak of it

irreverently — and donned in its place the prettiest little undress or forage cap imaginable —

the proper cap, be it observed, of the "Undecimo.”

1a. For information on Richard Bissington, hatter &

milliner, of Hull and Leeds, Yorkshire, see the Thoresby Society website. There is a photo of the Leeds branch on the

Leodis website.

2. "Labour

and the poor" [a straw plaiter interviewed in connection with Henry Mayhew's research] " Morning Chronicle - Friday 05 April 1850 p.5,

col.4. : "The little 'Jenny Lind' hats we get 4½d [about 2p

decimal] for. I dare say I could make three of them in a day. I never did much of

them though; they're for summer wear. Them very large broad brimmed ones as the children

wears they get 1s. 9d. [about 9p decimal] for making the finest quality,

some 1s.6d., [about 7½p decimal] some 1s.[5p decimal], and so on. It

all depends on the fineness of the plait; the courser the plait is, you know, the less time

it will take us to make it."

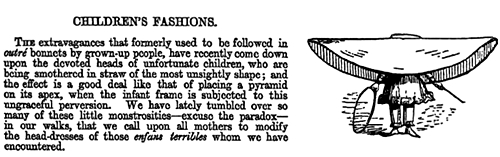

Jenny Lind hats for adults were smaller than some of the

children's hats at this time. In the late 1840s many children's hats became very

wide-brimmed, as noted in the exaggerated illustration (below) from Punch,vol 8. (1847),

p.28.

3. Le charivari — 28 August 1847

(col.3): "Certes la folie de la polka était bien grande à Paris,

il y a deux ou trois ans, mais ce n est pas à comparer au résultat des chansons de la prima

dona que la mode a prise sous sa protection. A Paris nous avons eu des habits polka et voilà

tout ; à Londres, toutes les modes sont à la Jenny Lind. Robe à la Jenny Lind, chapeau à la

Jenny Lind, faux-cols à la Jenny Lind, blague à tabac à la Jenny Lind."

4. Reminiscences of an 87-year-old lady, an

ex-resident of Haworth, in an article by C. Holmes Cautley: ‘Old Haworth Folk Who knew the

Brontës’. The Cornhill Magazine, New Series Vol. XXIX. July to December 1910.

pp.81-82. Smith, Elder, & Co., 15 Waterloo Place, London. Please note that in this article Mrs Ratcliffe's

"photograph on glass of the three sisters" is mentioned but this was an 1850s photo

of Branwell's 'Pillar' group portrait painting of the sisters.

5. Leeds Intelligencer - Saturday 23 September

1865, p.7.

"One of the most pleasing incidents of this

inspection was the appearance for the first time in Leeds of a vivandiere. She

marched in front of the regiment escorted by a Serjeant on each side, over the barrel

pier bridge, through the town to the Militia Barrack Yard in Carlton-lane, and was

very much admired by the tens of thousands who saw her, for her personal appearance,

the excellence of her style of marching, and her very modest

demeanour.

One of the officers of the Leeds

Engineers being in France a short time ago, and seeing a regiment of the line on the march

with a vivandiere in full uniform, marching at the head of the regiment behind the band,

was so much pleased with the evident usefulness of such an officer, that he volunteered to

supply the dress and accoutrements for one. A young lady undertook the office, her dress

was a copy from the uniform of the French vivandiere, but with the colours of the

engineers.

The jacket is scarlet with three rows

of silver buttons; petticoat Oxford grey with stripes of garter blue and scarlet ;

trousers, garter blue, with outside broad scarlet stripe; white shirt collar, with blue

tie; French white apron with pockets, and trimmed with blue and scarlet; white gauntlets

and kid gloves; straw hat covered with black oiled silk, and scarlet and blue cockade with

streamers; a regulation pouch belt to which was strung a barrel containing a quart of fine

old Cognac brandy; laced boots of black patent leather and red morocco.

Altogether her appearance was most prepossessing. When the

regiment marched past Col. Wombwell, the inspecting officer, in review order, she marched

alone in front of Lieut-CoL Child and Major Smith, and was much admired by all who saw

her.

It is to be hoped that at the next

review many volunteer regiments will have followed the example of the Leeds Engineers, and

that a regular staff of vivandieres will then be ready to assist in such cases of sudden

illness as took place at one of the reviews at Doncaster, when the services of two nurses

from the Leeds Infirmary had fortunately been previously procured."

|

|

|